For musicological purposes, if nothing else, I should write a few words about the experience of performing Julius Eastman's Gay Guerrilla with electric guitars. This work, along with its companion pieces Evil N****r and Crazy N****r, are ostensibly written for multiples of any instrument. At Northwestern in January of 1980, and at New Music America in Minneapolis in July of that year, Julius performed the piece with four pianos. Aside from those and our electric guitar rendition of December 14, I'm unaware of any other performances; I'd love getting information if anyone knows about any. I announced Thursday that that evening's performance might well have been the first since 1980.

With its long streams of reiterated notes, there are only a few instruments Gay Guerrilla could conceivably be played on. A Gay Guerrilla for oboes is unthinkable (one shudders to imagine). Mallet percussion is a possibility. Strings are too, though the notated pitches cover something like four octaves, so a full string ensemble would seem more appropriate than multiple violins. Pitches are supposedly transferable to any octave, but when Julius puts certain figures in notes below the bass clef, it's difficult to take that latitude too literally. The piece starts off with one line, and alternately expands and contracts up to nine; with four pianists, each obviously played more than one line. Luckily, we had nine guitarists, and two of those played bass guitars, which seemed the right percentage, though in some passages a third bass would have been welcome. In the piano version, the pianists would dot out the repeated pitches with the pedal held down. On guitars, the plucking of each note would damp the last, so we had to play a little more slowly to get a good resonance. Our first, too-quick runthrough sounded pretty pinched.

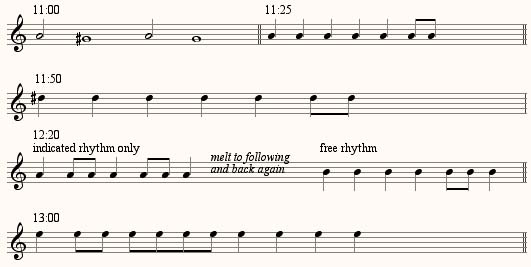

The original ms., dated September 1979, which we started out playing from a Xerox of, is sometimes cryptic. A real Downtown score, it needed not only to be interpreted, but deciphered. Each line contains figures to be repeated within a certain span of time, notated at beginning and end in minutes and seconds: often these figures are simply steady quarter- or 8th-notes, or else quarter-notes alternating or interspersed with 8th-note pairs. Inconsistency is rife. Sometimes bass clef lines are at the top of the system, above treble clef lines. The quoted tune "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" is notated with a bass clef, though the notes are clearly intended for treble clef (otherwise the tune would be D D D A# B# C# instead of B B B F# G# A#). Enigmatic notations appear. The students enjoyed an inscription that read "THE LESSING IS MIRACLE," and the music did indeed thin out at that point. Since the Xeroxes were 11"x17" with lots of unused space, I finally renotated the entire piece into Sibelius, and extracted individual parts, cutting 22 page turns (of 11"x17" pages) down to 5 (of 8"x11"). This involved considerable "orchestration" of the work, deciding which pitches to double when the number of lines would vacillate widely with no seeming concomitant change of dynamics. I'm afraid I don't remember how the doublings were decided 26 years ago. I may have to think of my version as just an "arrangement." Even with the inconveniences of the ms., though, students agreed that something was lost when we switched to the nicely printed Sibelius version, and the spirit of the piece became a little harder to capture.

At the NMA performance I had served as timekeeper by holding up pieces of paper that showed the onset time of each new system. Thursday night we used a computer-screen stopwatch instead, which was a convenient and much more elegant solution, with fewer visual cues to the audience as to what the mechanism was. Being able to anticipate the beginning point of each new line, the ensemble could mysteriously turn on a dime.

The performance was stunning, much louder than the piano version of course, and not so much sadly stern as menacing at times, almost like a Branca symphony - though without any urging from me the group took a restrained approach to volume. I kept thinking of Bruckner too (one of Branca's favorite composers), because of all the reiterative sonorities cycling through slow harmonic changes. There are passages in which the harmonies are dense and dissonant, and the loud guitars fused into a sound more than the sum of its parts; some reported audio illusions, thinking they heard voices. And the piece seemed to be virtually a universal favorite on the concert. My nine "gay gorillas," as I came to call them, worked hard and were dedicated to the piece, and deserve to be cited for participating in this historic occasion: Brian Baumbusch, Willy Berliner, Bernard Gann, Kenji Garland, Liam Hofmann, Narayan Khalsa, Anthony Kingsley, Jonathan Nocera, and Ezekiel Virant. Maybe they'll all be famous musicians themselves someday. If so I hope they'll notate a little more clearly than Julius did.

Copyright 2006 by Kyle Gann

Return to the Kyle Gann Home Page