Your generous responses to my little outburst about being tired of blogging certainly made it clear what most useful direction this blog can continue to go in. I may be out of ideas I haven't expounded, but my file cabinets and hard drives are still chockablock with music that's not in general circulation, and listeners are eager to have their experience widened. If I do no more than satisfy that longing, I will have felt that my trip to this planet was not in vain. If I become in the process sort of the Dick Cavett of avant- garde music, so be it.

One of the themes of my life has become something I never expected. I've based some large part of my career around documenting recent music not adequately represented by its score notation. It started with Nancarrow. His scores contain all of his notes, of course, but many of them, especially the late player piano studies, don't provide as much explicit rhythmic notation as is actually inherent. After some brief acquaintance with Nancarrow's music I formed a theory that, even when it looked like he was rather intuitively splashing notes onto the page, there was always some underlying tempo and even isorhythm to which everything referred. Some painstaking analysis with a little plastic millimeter ruler quickly bore me out, and I found further confi rmation when I was able to consult his punching scores - from which he made his final scores, but omitted the messy tempo-grid information.

Since then I have stumbled upon a wealth of music whose score notation, if it exists at all, doesn't adequately represent it. I reconstructed Dennis Johnson's November from the recording and score fragments, and have spent time transcribing improvisations by Harold Budd, Elodie Lauten, and others.

I've reconstructed some of Mikel Rouse's ensemble music from parts and mathematical models. Harry Partch's music is indecipherable as to pitch unless you know the various tablatures of his instruments, and, in the case of his Kitharas, I'm told that you can't figure out the music without knowing how to play the instrument.

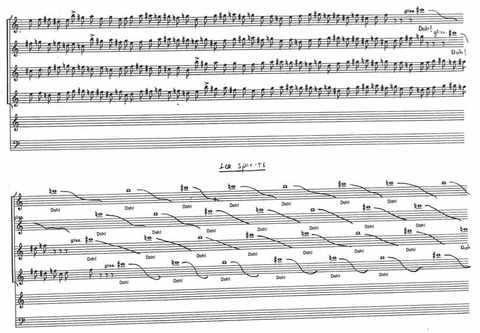

Lately I've finally been studying a rather sketchy 392-page score to Meredith Monk's 1991 opera Atlas that she was kind enough to give me years ago. Meredith refuses to have her singers learn music from notation because it detracts from a lively performance; she prefers to sing their lines and have them sing them back, as in Indian music. The Atlas score pretty much contains the instrumental parts verbatim, but some of the vocal parts are left blank on the page, indicating that they were to be developed in rehearsal. Scores to two of the most beautiful sections, "Choosing Companions" and "Agricultural Community," contain no vocal parts at all. The "Ice Demons" music, when compared with the recording, shows how precise some of her notation is, how free it is in other places, and how free the singers were to ignore it in either case:

The whole score is a fascinating document of Meredith's working method. Occasional passages are blanked out, omitted in rehearsal, and where the vocal rhythms (heard here) are exactly notated, the actual performance is often much freer:

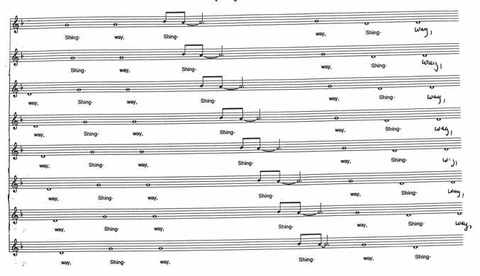

It's difficult to imagine improving on the unconventional notation of the "Shing Way" section, in which the singers sit in a circle and pass each pitch or figure linearly from one to another (recording here):

I don't know whether, since 1991, Meredith has made a nicer, more complete score of Atlas, but why should she? This was adequate for a series of stunning performances, and it represents a starting point for the piece, not an end product in itself. Some musicologist could certainly prepare a nice final score using this and the recording as guides, but this one tells more about Meredith's working method than an engraved Universal Urtext ever could.

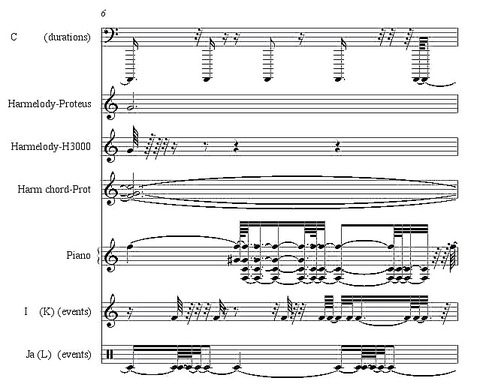

The lack of scores is a big issue for studying Robert Ashley's music as well; or rather, the discrepancy between his spare working scores, his "production notebooks" as he calls them, and the information overload on the recordings. Years ago when I analyzed Improvement: Don Leaves Linda with a class, Bob kindly gave me the complete MIDI les for the piece, but correctly warned me that they wouldn't be much help. They were used to trigger events in primitve 1980s software that no current computer still supports, and it's only here and there that one nds telling correspondences between the MIDI and the recording. Translated to notation, the MIDI files look something like this:

It's possible that some tracks triggered only markers heard by the performers through headphones, and not by the audience.

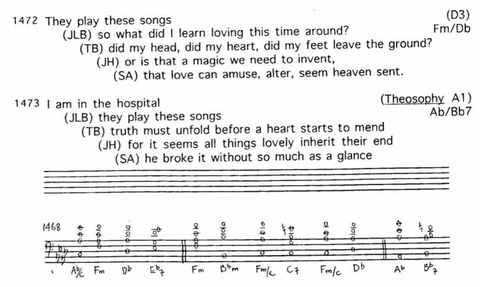

More typically, Ashley's actual scores contain the libretto marked out in numbered lines, surrounded by harmonic or melodic notations where needed, like this page from Dust:

Ashley takes on the problem of how someone else could perform his operas in an article called "Style and Technique: Performance Practice," which is collected with his other writings in a dazzlingly huge and mind-challenging new collection of his writings from MusikTexte titled Outside of Time: Ideas about Music, which I will surely be writing more about later. "The solution," he writes,

"is to get all of the operas recorded in a finished form in the most recent format (now, compact discs). Anybody who wanted to produce one of the operas could work from the compact disc, which represents the way the opera is to be performed and how it is supposed to sound. Except for the rhythmic treatment of the words, which remains a notated constant, there is no score from which to make the orchestra. As I have said, the studio production notes for any opera will make little sense in the future, even if I could decipher them now, because they refer to instruments that will be long gone.

He talks about a student writing a dissertation on Perfect Lives, to whom he had to explain that a score did not exist.

" ...about two months later I got in the mail a very accurately transcribed orchestration of the first episode of Perfect Lives, "The Park."

This is how it should be. The person listened. This is how jazz musicians learn jazz. This is how most of the people in the world learn the music they play. [p. 190]

Like Ashley, Mikel Rouse has a ton of MIDI information in his scores that can't be deciphered without access to his hardware setup, and can only be documented by reference to the recording. The "chromaticism" in his unpitched percussion parts in this measure from Dennis Cleveland is a dead giveaway:

I also have a pile of one- or two-page scores by David First that I hope to get to someday, marked with little more than noteheads and plus-or-minus-cent numbers. The following page seems to comprise the 15-minute entirety of his piece Distance Receives Permission to Enter from the album Resolver:

You can listen along and follow the whole piece here. I doubt there's much danger of someone taking the score and arranging a performance independently.

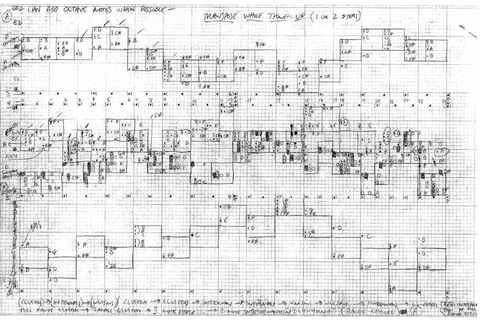

Finally, here's an intriguing passage, with Totalist rhythms, from Glenn Branca's Symphony No. 6 for electric guitars, back from his pre-musical-notation days:

In a way there's a mirror image here, within academic discourse, to 12-tone music. Twelve-tone music and its related forms inspired an immense music-theoretical literature devoted to explaining how the music, opaque as it often is to the ear, is made, and by extension how it is to be heard. Minimalism and its related forms are likewise inspiring a new literature in musicology, for scholars simply trying to document what the music consists of. Famous pieces can be reconstructed from recordings. Partch's scores get published in just-intonation-notation transcriptions. Even Steve Reich's celebrated Music for 18 Musicians was apparently notated so idiosyncratically that younger composer Marc Mellits had to do considerable work on the score to make it publishable by Boosey and Hawkes.

The music is worth analyzing. But it is not the composer's responsibility to make it available for analysis - it is his or her responsibility to successfully bring it to performance. If more is needed for teaching purposes, there are musicologists. As Cage would have added: use them.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Of course, scores like these pose a pedagogical problem. They depart from the universal paradigm for what a score is: a linear continuity on bound paper which contains all the information needed to replicate the piece in performance. The central core of the composition teacher's job is to teach a student how to write self-contained music for strangers to play. Students have often told me the goal as other teachers have stated it to them: your score should be so detailed and self-explanatory that you can mail it to an ensemble in Japan who are unfamiliar with your music, and they'll be able to send you back an accurate recording. Of course, I find this ideal illusory at best. I've sent pretty clear scores to friends who know my work well, and shown up for rehearsal to find energy levels and tempos all wrong, even with dynamics and metronome markings quite explicit. The truth is, traditional musical notation is at best never an entirely efficient transmitter of an imagined musical sound object. The participation of the composer is omitted at everyone's peril.

The other truth is, music is not necessarily an imagined sound object (though in academia it is often assumed to be only that). Often it is the result of a process, and emerges only in rehearsal. And the intense conformity to expectation involved in learning to make a detailed conventional classical score is a great reiner-in of imagination and individuality. I see my students wrestle, touchingly, with this problem every year. Some of them are eager to write for orchestra and other conventional classical ensembles, and they want to be taught to notate by the book. Others are used to working in rock bands and alone and with friends, and they have effects they want to try out, experiments they want to conduct in rehearsal, parts that they want to leave to improvisation, rhythmic effects that just won't conform to a notated meter. Some of them come up with pretty idiosyncratic notations, but they play the pieces and get what they want. Then they decide that they can't resist that opportunity to write for orchestra for their senior project, and I have to explain at great length what they can expect to achieve with a conventional orchestra in 20 minutes' rehearsal. They want to put radios in the orchestra, have the players shake boxes of metal debris, improvise with the orchestras at different tempos under two conductors, and so on. (We did manage an ampli ed toy piano in the orchestra one year.) But the classical performance paradigm is an assembly line, and much of composition pedagogy is involved with teaching them, and limiting them to, what can be achieved by players basically sight-reading what's been plopped on their music stands. I never push - but some of them decide not to curtail their individuality for the assembly line, and I applaud them after they make the decision. It takes courage.

As one disaffected young composer recently wrote to me about his crucifixion in the academic milieu, "There is no career success outside this horseshit, and no artistic success within it." That's pretty close to the truth. But in the long run Ashley and Monk and Rouse have managed pretty enviable artistic lives by working outside the system. It takes a kind of relentless heroism.

So you don't like the words Uptown and Downtown: fine. But if you deny the existence of this division in order to erase from your consciousness the fact that some of the most creative and original of recent composers have gone outside the classical paradigm to escape its stultifying limitations, then you delude yourself. Our new music suffers more than anything, I think, from a relentless conformism pushed on young composers in the name of "professionalism," and conformity does not excite audiences. Perhaps we can begin by de-fetishizing the printed score and admitting that it is only a tool, and not always a complete or even necessary tool, that it can sometimes be thrown away once the music exists. Making scores like the above examples available as models for how to go outside the norm, and analyzing the music that goes with them as best we can, may be a start.

Copyright 2010 by Kyle Gann

Return to the Kyle Gann Home Page