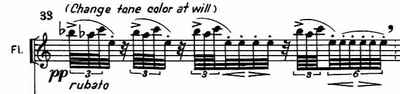

I've loved George Rochberg's Serenata d'Estate (Summer Serenade) since I was in high school. Yesterday, for the first time, I finally analyzed it in the classroom. The little repeated-note gestures in the senza battute sections:

have always reminded me of similar figures in George Crumb (Eleven Echoes of Autumn, Mikrokosmos I, and other works):

In fact, such figures don't appear again in other Rochberg works I know (though I'm sure I've heard only half of his output at best), but they become very important in Crumb's 1970s music. Rochberg wrote Serenata d'Estate in 1955 and came to the University of Pennsylvania in 1960; Crumb joined the faculty there in 1965, and wrote Eleven Echoes that year. I wonder if there's a connection.

Likewise, the hypnotic repetitions in Serenata d'Estate:

are extremely unusual for a period that eschewed repetition. They remind me very much of repetitions in Feldman's Structures for string quartet of 1951:

Rochberg spent the 1950s as an editor for Theodore Presser, but Structures doesn't seem to have been published until 1962, and it's hard for me to imagine Rochberg would have heard it. But it's curious, two composers so disparate in background having written repetitively static music, in implied triple meters with cross-rhythms yet, in an era that was virtually hostile to such an idea.

Some of the students in my 12-tone class, once they realized what 12-tone music is, attempted to flee, but couldn't find other classes to get in to, so now they're a captive audience. Serenata d'Estate was the first piece that met with general approval; Rochberg's Second Symphony was the first to elicit a unanimous roar of enthusiasm. The other piece I will have spent more than two hours analyzing at the blackboard this week, in my Beethoven class, is the Archduke Trio, one of the most perfect pieces ever written, and another one that I've never had the opportunity to analyze in depth until now. It's been years since I've been so involved in the material I'm teaching.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

COMMENTS:

Richard says: Kyle, I think there must have been something in the air. As a kid I was much taken with the "Philly School" (Crumb, Rochberg and Wernick) and even thought of studying at U. Penn. (I didn't) Listen to "The Silver Talons of Piero Kostrov" and you can hear that Rochberg was working in a sound world quite similar to that of Crumb (and Wernick). The same, I think, can be said of Foss's "Time Cycle". In some ways, I think the Philly School were among the first to take on the hidebound conservatism of the academic composer mafia. They really were a breath of fresh air for the east coast establishment. You might even call them the first "downtown" composers.I could go on but I don't like wasting folk's time.

KG replies: You never waste *my* time, Richard. These kinds of issues get discussed far too infrequently and never at enough length.James Primosch says: Having studied with what we used to call the Penn Troika, and having played the music of two of them, I can say that there were definitely cross-influences. Sometimes this refers to obvious stuff like the instrumentation - their love of crotales, for example. Crumb's "Lux Aeterna" and Wernick's "Kaddish-Requiem" both use sitar and date from a moment when there was a sitar teacher across the hall from their offices at Penn. All three composers made use of quotation of earlier musics. Sometimes the cross-influences can be seen in the use of musical shapes like the repeated notes you mention. I don't think it is repeated notes specifically, but more the use of short, repeated, highly characterized gestures - a kind of motto or signal. The opening of the Rochberg Third Quartet is an example, so is the beginning of his "Carnival Music" for piano. They are all over the place in Crumb. In Wernick's music, not so much. I think with Rochberg the use of repeated gestures has to do with the tendency (as he saw it) of twelve-tone music toward harmonic stasis; it also has to do with Varese. With Crumb the use of motto-like gestures relates to the "night music" movements of Bartok - the one in "Out of Doors" really sounds like a Crumb piece! All three composers contributed to the genre of "apocalyptic" pieces that I think were a product of living in the shadow of The Bomb in the Cold War era, but there were certainly other people writing such music - Don Erb's "The Seventh Trumpet" comes to mind. All three men used extended performance techniques - most notably, the inside the piano writing in the work of all three. Compare Crumb's "Eleven Echoes of Autumn" with Rochberg's "Contra Mortem et Tempus" - both written for the Aeolian Chamber Players. I agree with Richard's comment about these Penn composers seeking a fresh path (not so sure about the "mafia" reference), but they tried to renew the use of regular pulsation and a less chromatically saturated harmony (goals they shared with minimalists) by connecting with earlier musics - 20th century modernist classics (Bartok, Debussy, Ives) and tonal music. In one class Rochberg had us write 19th century piano style-studies, and in composition seminar we studied Mahler symphonies. In this sense the Penn Troika was not a proto-"downtown" enterprise, (I assume Richard in his comment meant "downtown", not "uptown") but more of a "pre-post-classic" one. Your comparison of the "Serenata" with Feldman's quartet is intriguing, but I doubt Rochberg was influenced by Feldman, even though their musics may, for a moment at least, have intersected. Sadly, Rochberg's relationship with Crumb's work was not unclouded. In his memoirs, Rochberg refers to how hearing Crumb's "Black Angels" showed him what he did *not* want to write in his Third Quartet - yet the two pieces have several important points in common. In another place in the memoirs, Rochberg claims to have "invented" the piano harmonics that I am pretty sure Crumb had already employed. (I've written about the Rochberg memoirs on my blog.) I also love the Rochberg 2nd Symphony and the "Serenata", and I agree that students tend to find these pieces attractive as well. Thank you for writing about them, Kyle.

KG replies: Fascinating. I take it Karel Husa was part of that apocalyptic moment as well.Copyright 2010 by Kyle Gann

Return to the Kyle Gann Home Page