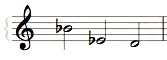

I don't know if this constituted a great moment for my students, but it did for me. My favorite piece by the British postminimalist Gavin Bryars, although I doubt that I've heard everything he's recorded, has always been his 1990 piece for ballet Four Elements. I once started analyzing it on my own and didn't get far, but we spent our entire minimalism class (two and a half hours) on it the other day, and I was quite impressed with what we found. The entire piece is drawn from a three-note motive heard in the chimes in the first two measures, a fifth and a minor second:

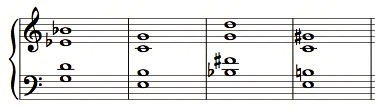

(echoed by the vibraphone in the next phrase, G-C-B). All of the harmonies of this half-hour piece are drawn from this motive, in the form of two fifths separated by a half-step between the bottom note of one and the top note of the other. However, while most of the fifths are perfect, sometimes either the lower or higher one is augmented (Bb-F# and C-G# here):

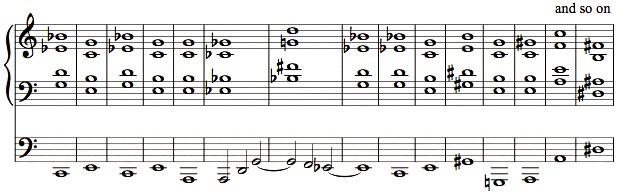

The perfect fifths make either a major seventh chord or a minor triad with a flat 13th, depending on what is emphasized in the bass; the others can be an augmented seventh or a minor triad with a major seventh. The piece capitalizes well on the major/minor ambiguity inherent in these voicings. Of course, any seventh chord can be spelled as two fifths, but this is the way Bryars voices them in the piano and electric keyboard parts, and the melodies in the winds frequently bring out the fifth- (or fourth) plus-half-step motive. In addition, the harmonic feel of these chords can be altered by whatever note is additionally heard in the bass. The elements are in the order water/earth/air/fire, and the opening water movement is built on the following chord progression:

Note, for instance, that the fifth keyboard chord is the same as the second and fourth, but has a quite different feel with the A in the bass rather than the E. The intuitive, meandering quality of this progression, with some chords being sustained over more than one bass note, is the reason I never got very far with the piece in the beginning. But in class we looked at the second section (earth) and found the identical progression, more systematically articulated in repeated 16th-note patterns. The third section (air) begins with a different but related chord progression (shown below), but brings back this above progression toward the end.

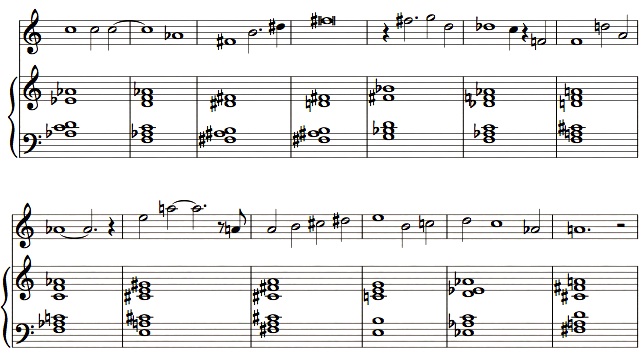

Here is the recording (ECM, conducted by Roger Heaton) of the first section and the beginning of the second. We had a good discussion in class about why the piece doesn't sound particularly minimalist or postminimalist. Part of it is the foregrounded and highly expressive melody in the bass clarinet. Another part is that, unlike in most minimalist-related music, the harmonies don't sound functionally equivalent. Because of the augmented fifths and the variable and sometimes dissonant bass notes, there are purposeful-sounding gradations in the calmness or intensity of the chords, which give the piece a more uneven emotional shape than is common in minimalism. And yet, the harmonic rhythm is pretty regular, either two measures per chord or in some sections three; and the way I'm aurally programmed I still hear the piece as postminimalist because of the way the melodies sound derived from the harmony rather than vice versa, drawing the chromatic connections between distantly related chords in exactly the way Glass does in the "Bed" scene of Einstein on the Beach. Most obviously, here's the opening alto sax melody with chords from the Air section, and you can hear the audio here:

Perhaps it's only because I am so attuned to noticing how minimalist music operates beneath the surface that I hear this piece as minimalist. The analysis confirms my impression that the harmonies may have been composed first and the melody laid over it; at least it sounds like it's the harmony that drives the music. I do something similar in the nal movement of my Transcendental Sonnets, a nine-minute chain of seventh chords, although determined via parsimonious voice-leading rather than intervals or root movement. And I didn't have to go to Gavin Bryars for the idea, it was all implicit in Einstein. Still, that's a quintessentially Gannian kind of melody in that example. No wonder I love the piece.

One of the things that I love about teaching minimalist music analytically is that it's such a good pedagogical model for young composers. When I was an undergrad I was trying to mimic Boulez and Berio, and I didn't have nearly enough technique under my belt to achieve anything close to their complexity and subtlety; I hadn't "come up through the ranks" on that complicated history. But minimalist pieces tend to be clear in their structure and often deceptively obvious in their procedure once you look just beneath the surface. They embody a level of technique that students truly could imitate and pull off, and while some will take that as a criticism of the music, it's not. The pieces are attractive and remain so after years of listenings, and the students are thrilled with them. But such minimalist pieces often draw tremendous length from very little material, which, if I remember my history of musical aesthetics correctly, used to be considered quite a virtue (see Bach, J.S., and Webern, Anton, for instance). I would love to command a composition student, "Pick three notes and write an entire 30-minute ensemble piece using only patterns derived from them," and then show him or her that Bryars did exactly that, with stunning results. It's such a great repertoire for a student to start out with, and if they want to do something more complicated later, they can always move on. Personally, I would find this rich kind of simplicity enough to aim for.

Copyright 2013 by Kyle Gann

Return to the Kyle Gann Home Page