Kyle Gann: Proença

(2015)

for alto voice, flute, vibraphone, electric piano, electric bass

Be.m pac d'ivern

Na Audiart

Alba (En un vergier sotz fuella d'albespi)

Estat ai en greu cossirier

L'aura Amara

Near PerigordProença (2015)

Sir Bertans de Born started it. Around 1182 or earlier he wrote a striking poem, "Dompna, puois de me no.us chal," addressed to a lady, named Maent (in Pound, though the original was Maeut, cognate with Maud), who had withheld her affections from him. In it, Bertrans (pictured at war on right) says that since Maeut scorns him, he will make up an imaginary perfect lady by picking the best qualities of all the other ladies in surrounding castles: Bels Cembalins's complexion, Midon Aelis's cunning speech, the supple body of Miels-de-Ben, and so on. The poet Ezra Pound (1885-1972), one of the great early scholars of troubadour poetry, formed a theory (based on local geography, misinformation, false chronology, and sheer imagination) that "Dompna puois" was a covert political strategy; that Bertrans's castle was surrounded by enemies all connected to the family of Tairiran (later Talleyrand), and that by praising these ladies he was seeking to form political alliances, and to set the castles against each other. However misplaced Pound's speculations, Bertrans did take sides with Henry II in revolution against the latter's father, for which Dante (1265-1321) placed him in the eighth circle of hell in his Inferno, as a "stirrer up of strife."

His imagination sparked by the figure of Sir Bertran(s), Pound wrote not only a translation of "Dompna puois" but two poems heavily alluding to that poem, Na Audiart (1908) and Near Perigord (1915). Musical settings of these two poems form the frame of my song cycle Proença. I became rather obsessed with Pound in college, and with medieval music as well, resulting in a lifelong fascination with the troubadours, the singer-songwriters of 12th- and 13th-century Provence. The troubadours and Pound both fascinate me, but what I find most intriguing is the idiosyncratic view we get of the troubadours through Pound's eyes. In March 2015 the singer Michelle McIntire asked me to write her something; she has a wide range but a low tessitura, and her sultry register brought the troubadours to mind. For some reason I had never thought about setting Pound before, but the idea took root quickly, as though it had been long overdue. I went rather overboard, envisioning Na Audiart as a kind of dark jazz ballad by a scorned lover, and then adding more and more songs as each poem led to another. (The range of the cycle is almost two octaves Ab to G, but the tessitura resides in the octave above middle C, and there are more extended passages below that than above it.)

A perhaps obligatory note: I mentioned to a famous poet that I was writing a song cycle on Ezra Pound, and she shouted, "That bastard!" I know. I have long felt that there is no point in blaming the art for the personal faults of the artist. For the record, I have neither interest in nor sympathy for the "man-of-action" theories that led Pound (relegated in recent decades to his own eighth circle of hell) to first champion de Born and later Mussolini for similar reasons. The texts I've used, all 1917 or earlier, predate the disillusionment that followed World War I and Pound's turn toward unpalatable views of society - views that he himself renounced late in life. The poetry is wonderful and, I think, innocent.

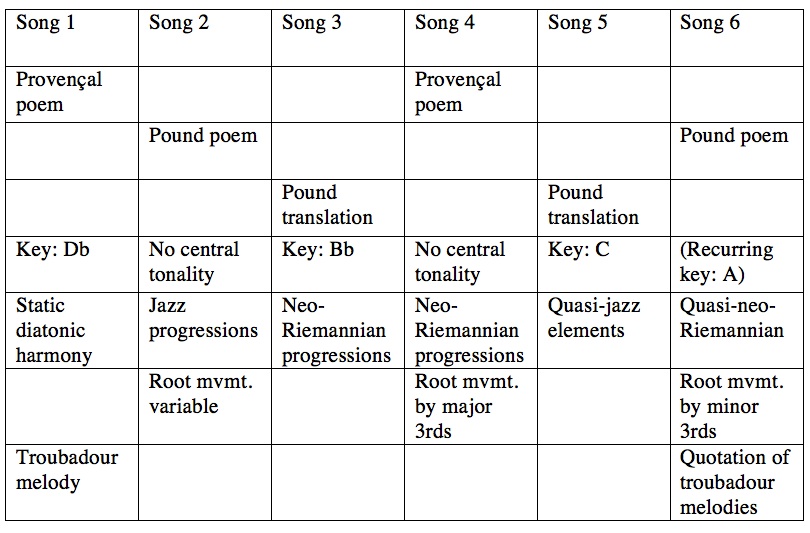

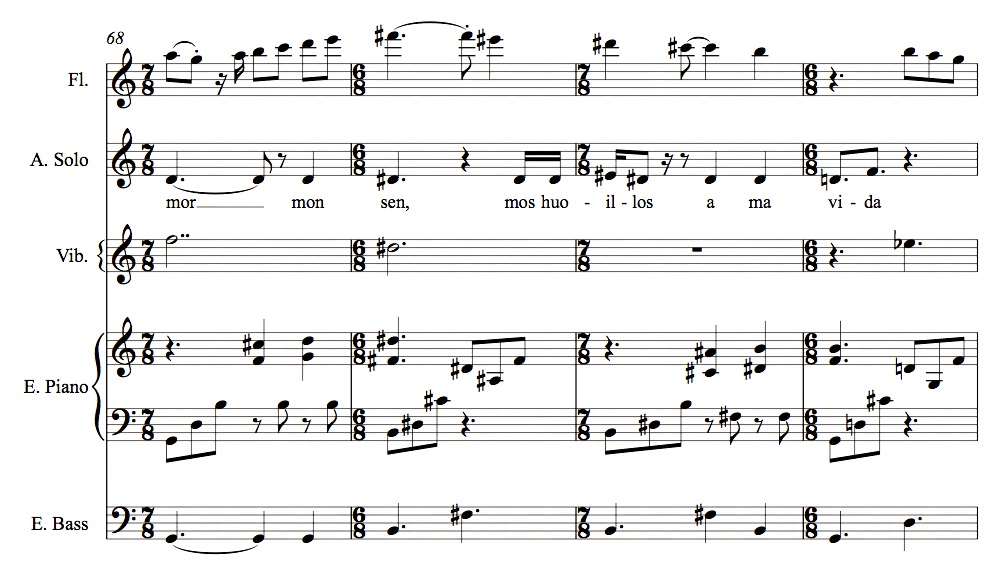

Proença comprises two troubadour songs (nos. 1 and 4) in the original Provençal (one with the original tunes); two translations of troubadour poems by Ezra Pound (nos. 3 and 5); and the above-mentioned two poems by Pound about Bertrans de Born (nos. 2 and 6). This is one of several levels of symmetry noticeable in the following chart:

In addition, the 1st, 3rd, and 5th songs are set in a single, unchanging tonality; the 2nd, 4th, and 6th have no central key. Songs 3 and 4 are characterized by neo-Riemannian chord progressions (closely chromatic voice-leading), one in the context of a stable tonality, the other in a kind of free-floating (though consonant) atonality. Song 2 uses more of a jazz sense of progression; Song 5 has jazz elements in the harmony as well, though it doesn't change key. In Song 4 the root movement is mostly by major 3rds, in Song 6 it is mostly by minor 3rds. Actual troubadour melodies are quoted only in Songs 1 and 6, foregrounded in the former and backgrounded in the latter. Songs 1 and 3 both follow a kind of additive process, 1 and 4 share an articulated steady pulse, 1 and 5 share a pointillistic texture. Songs 1, 3, 4, and 5 are stanzaic, and I handled stanzaic form four different ways:

Song 1: Static accompaniment, three different melodies

Song 3: Melody becomes more developed with each repetition; final envoi switching to a slower tempo

Song 4: Through-composed, no repetition

Song 5: Repetition of both melody and accompaniment; final envoi switching to a homophonic textureThere are other, smaller ways in which the songs echo each other. I planned out none of this structure in advance, but kept adding new poems as I instinctively felt gaps in the overall conception. There is no particular narrative arch to Proença, but this is typical of how I tend to create variety in a multimovement piece, mixing and matching an array of qualities from movement to movement for a gradually shaded set of perspectives on similar material.

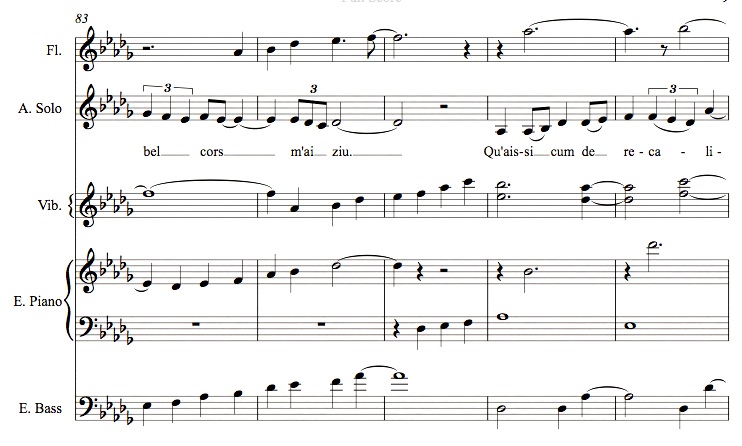

1. Be.m pac d'ivern - Peire Vidal's "Be.m pac d'ivern," written before 1180, has long struck me as the most fascinating troubadour melody, for its large range (an octave plus a minor seventh), its rising pentatonic motives, and its fluid mix of syllabic and melismatic writing. (Writing on a four-line staff, the scribes had to keep changing clefs every few notes.) It's kind of a textual nightmare, though, because it appears very differently in the three manuscripts in which it survives: Paris, Biblioteque Nationale f.frcs. 22543 (called manuscript R, pictured), Paris, Biblioteque Nationale f.frcs. 20050 (manuscript X), and Milano, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, R71 sup. (manuscript G). Rather than create an ideal melody by mixing and matching phrases, as some performers have, I decided to set all three manuscripts in sequence, in the order X, R, G. The X and G versions have similar contours; that in R has a narrower range and less florid ornamentation, and thus my setting has something of an ABA form. Thanks to the indispensable Carson Cooman for help with research.

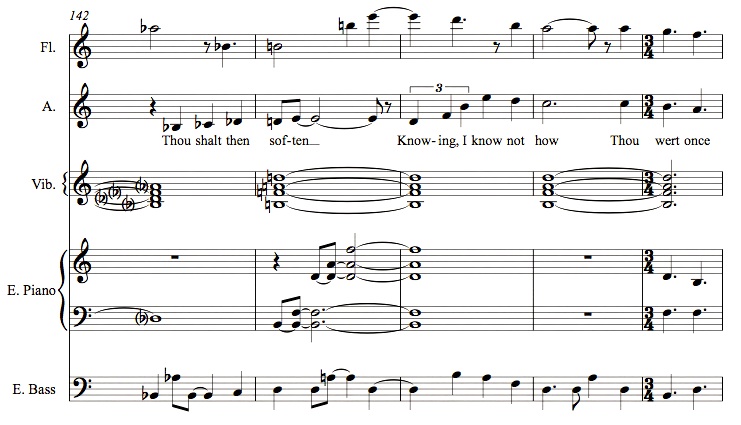

2. Na Audiart (1908) - This sardonic Pound poem, with allusions to de Born's "Dompna, puois," is addressed to Lady Audiart of Malemort castle, whose slender form the protagonist praises despite knowing that she wishes him ill.

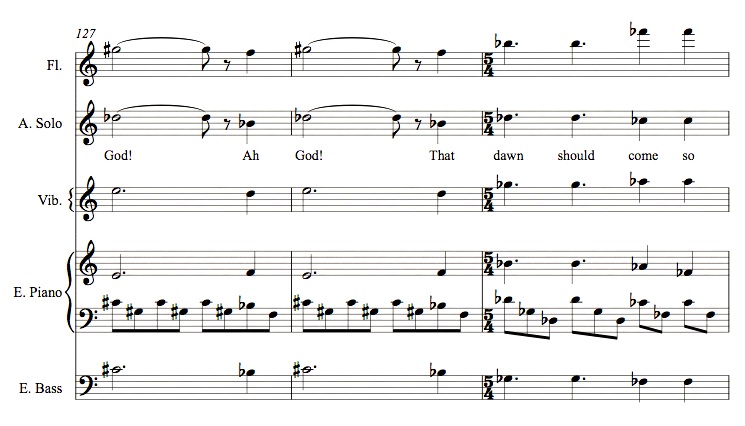

3. Alba (En un vergier sotz fuella d'albespi) - I wanted to include an alba, one of the most common troubadour types, a formulaic medieval song form warning two lovers who shouldn't be found sleeping together that the dawn is imminent. Pound claims that the best one ever written is the anonymous "En un vergier sotz fuella d'albespi," and so I chose his 1909 translation of that.

4. Estat ai en greu cossirier - Also, since this cycle was written for female voice, I wanted one poem written by a woman. The Comtessa de Dia (late 12th-century) is the most famous woman troubadour, and while the lovely tune of her "A chantar" is preserved and widely performed, I wanted to write an original without being conscious of the pre-existing tune, so I chose her "Estat ai en greu cossirier," for which no melody survives. In it she mournfully cajoles a lover who had given up on her. It is sung in the original Provençal.

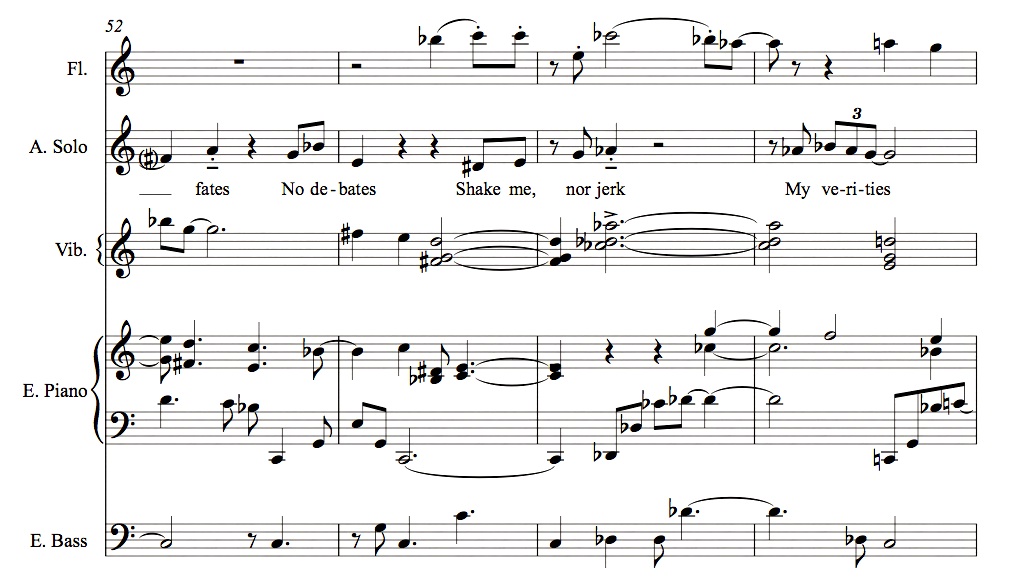

5. L'aura amara - Pound's idiosyncratic 1917 translation of "L'aura amara" by Arnaut Daniel - a troubadour mentioned and used as a character in Near Perigord - has always thrilled me with its near-incomprehensible attempt to turn Arnaut's complicated rhyme scheme into prickly vorticist modernism. I created for it a melodic form that works against the fragmentation of the lines, and that I hope makes the poetic form audible.

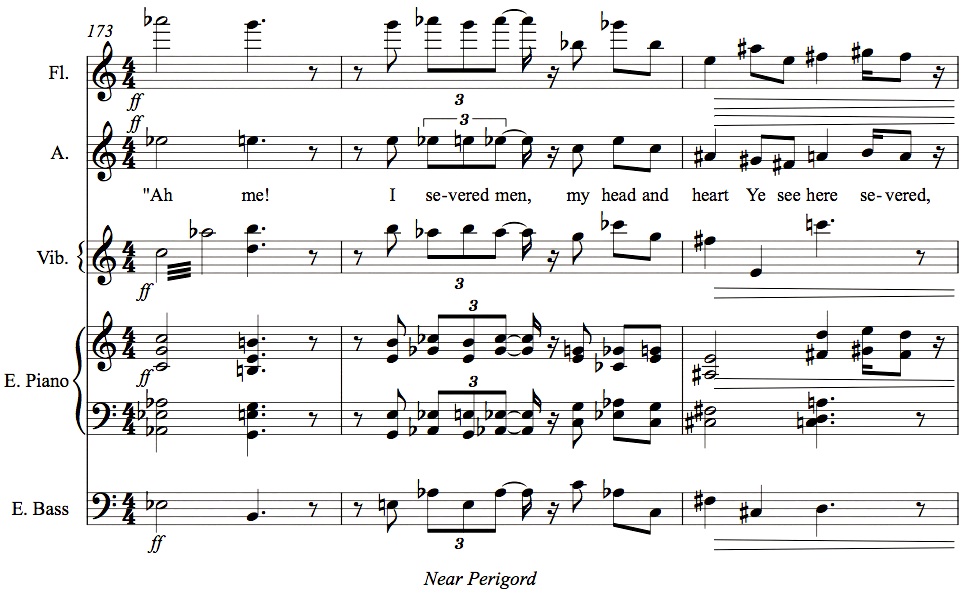

6. Near Perigord - The culmination of the cycle is Pound's magnificent Near Perigord (1915), his musing on Bertrans's motivations and actions, with a climax quoting Dante's picture in the Inferno. The entire poem would take a half hour to sing, so (as Pound himself greatly abbreviated Dante's lines) I cut down its 1500 words to about half of that, fashioning a libretto for a kind of historical tableaux - regretfully omitting Pound's redundancies, asides, and more circuitous descriptions. Quotations in the poem are set off as speech-rhythmed unisons in the music, partly as a reference to the fact that all we know of troubadour melody is its pitches, and the rhythms are alway conjectural. Two troubadour melodies are quoted in the flute, one near the beginning -"Tres enemies e dos mals segnors ai" by Uc de St. Circ, who is mentioned in the poem for having written Bertrans' vida - and in the middle and near the end, "Rassa tan creis" by Bertrans himself. (In addition, there is a reference in the text to Ventadour, by which I think Pound means the castle of that name, not Bernart de Ventadorn who hailed from it; but just in case, I worked some turns from Bernart's famous song "Can vei la lauzeta mover" into the melody.)

I began the cycle on March 30, 2015, and completed the final revisions on June 27.

Texts:

Peire Vidal: "Be.m pac d'ivern"

Be.m pac d'ivern e d'estiu

E de fregz e de calors,

Et am neus aitan cum flors

E pro mort mais qu'avol viu,

Qu'enaissi.m ten esforsiu

E gai Jovens et Valors.

E quar am domna novella,

Sobravinen e plus bella,

Paro.m rozas entre gel

E clar temps ab trebol cel.Ma don'a pretz soloriu

Denant mil combatedors,

E contra.ls fals fenhedors

Ten establit Montesquiu:

Per qu'el seu ric senhoriu

Lauzengiers non pot far cors,

Que sens e pretz la capdella!

E quan respon ni apella

Siei dig an sabor de mel,

Don sembla Sant Gabriel...Per zo.m ten morn e pessiu,

aitant quant estauc alhors;

pueis creis m'en gaugz e doussors,

quan del sieu bel cors m'aiziu.

Qu'aissi cum de recaliu

ar m'en ven cautz, ar fredors;

e quar es gai'et isnella

e de totz mals aips piucella,

am la mais per San Raphel,

que Jacobs no fetz Rachel...Translation by Linda M. Paterson: I. I am happy with winter and summer and cold and heat, and I like snow as much as flowers and a dead hero more than a live villain, for this is how youth and worth keep me keen and joyful. And because I love a fresh young lady, supremely delightful and most beautiful, I see roses in the ice and fine weather in cloudy sky.

II. My lady has unique merit in the face of a thousand assailants, and she holds Montesquieu fortified against the false hypocrites: so a slanderer can make no inroad into her noble realm, for wisdom and merit guide her; and when she responds or calls her words taste of honey, which makes her seem like St Gabriel.

V. Whenever I am away from her she keeps me sad and pensive; then when I draw near to her lovely person I am filled with joy and sweetness. Like a man in a fever I go hot and cold by turns; and since she is merry and vivacious and pure of all bad qualities I love her more, by St Raphael, than Jacob did Rachel.Ezra Pound (1885-1972): Na Audiart (1908)

Though thou well dost wish me ill

__________Audiart, Audiart,

Where thy bodice laces start

As ivy fingers clutching through

Its crevices,

__________Audiart, Audiart,

Stately, tall and lovely tender

Who shall render

__________Audiart, Audiart,

Praises meet unto thy fashion?

Here a word kiss!

__________Pass I on

Unto Lady 'Miels-de-Ben',

Having praised thy girdle's scope

How the stays ply back from it;

I breathe no hope

That thou shouldst . . .

__________Nay no whit

Bespeak thyself for anything.

Just a word in thy praise, girl,

Just for the swirl

Thy satins make upon the stair,

'Cause never a flaw was there

Where thy torse and limbs are met

Though thou hate me, read it set

In rose and gold.

Or when the minstrel, tale half told,

Shall burst to lilting at the praise

__________"Audiart, Audiart" . .

Bertrans, master of his lays,

Bertrans of Aultaforte thy praise

Sets forth, and though thou hate me well,

Yea though thou wish me ill,

__________Audiart, Audiart.

Thy loveliness is here writ till,

__________Audiart,

Oh, till thou come again.

And being bent and wrinkled, in a form

That hath no perfect limning, when the warm

Youth dew is cold

Upon thy hands, and thy old soul

Scorning a new, wry'd casement,

Churlish at seemed misplacement,

Finds the earth as bitter

As now seems it sweet,

Being so young and fair

As then only in dreams,

Being then young and wry'd,

Broken of ancient pride,

Thou shalt then soften,

Knowing, I know not how,

Thou wert once she

__________Audiart, Audiart

For whose fairness one forgave

__________Audiart,

Audiart

_____Que be-m vols mal.En un vergier sotz fuella d'albespi

Ezra Pound translation, 1909In a garden where the whitethorn spreads her leaves

My lady hath her love lain close beside her,

Till the warder cries the dawn - Ah dawn that grieves!

Ah God! Ah God! That dawn should come so soon!"Please God that night, dear night should never cease,

Nor that my love should parted be from me,

Nor watch cry 'Dawn' - Ah dawn that slayeth peace!

Ah God! Ah God! That dawn should come so soon!"Fair friend and sweet, thy lips! Our lips again!

Lo, in the meadow there the birds give song!

Ours be the love and Jealousy's the pain!

Ah God! Ah God! That dawn should come so soon!"Sweet friend and fair take we our joy again

Down in the garden, where the birds are loud,

Till the warder's reed astrain

Cry God! Ah God! That dawn should come so soon!"Of that sweet wind that comes from Far-Away

Have I drunk deep of my Beloved's breath,

Yea! of my Love's that is so dear and gay.

Ah God! Ah God! That dawn should come so soon!"_____Envoi

Fair is this damsel and right courteous,

And many watch her beauty's gracious way.

Her heart toward love is no wise traitorous.

Ah God! Ah God! That dawn should come so soon!Comtessa de Dia: "Estat ai en greu cossirier"

Estat ai en greu cossirier

per un cavalier qu-ai agut,

e vuoil sia totz temps saubut

cum ieu l'ai amat a sobrier;

ara vei qu'ieu sui trahida

car ieu non li donei m'amor

don ai estat en gran error

en lieig e quand sui vestida.Ben volria mon cavallier

tener un ser en mos bratz nut,

qu'el s'en tengra per ereubut

sol qu'a lui fezes cosseillier;

car plus m'en sui abellida

no fetz Floris de Blanchaflor:

ieu l'autrei mon cor e m'amor

mon sen, mos huoillis e ma vida.Bels amics avinens e bos,

cora.us tenrai en mon poder?

e que jagues ab vos un ser

e qu'ie.us des un bais amoros;

sapchatz, gran talen n'auria

qu'ie.us tengues en luoc del marit,

ab so que m'aguessetz plevit

de far tot so qu qu'ieu volria.Translation by Meg Bogin:

I've lately been in great distress

over a knight who once was mine,

and I want it known for all eternity

how I loved him to excess.

Now I see I've been betrayed

because I wouldn't sleep with him;

night and day my mind won't rest

to think of the mistake I made.How I wish just once I could caress

that chevalier with my bare arms,

for he would be in ecstasy

if I'd just let him lean my hand against his breast.

I'm sure I'm happier with him

than Blancaflor with Floris.

My heart and love I offer him,

my mind, my eyes, my life.Handsome friend, charming and kind,

when shall I have you in my power?

If only I could lie beside you for an hour

and embrace you lovingly -

know this, that I'd give almost anything

to have you in my husband's place,

but only under the condition

that you swear to do my bidding.

Arnaut Daniel: "L'aura amara"

Translation by Ezra Pound (1917)The bitter air

Strips panoply

From trees

Where softer winds set leaves,

And glad,

Beaks

Now in brakes are coy,

Scarce peep that wee

Mates

And un-mates.

_____What gaud's the work?

_____What good the glees?

What curse I strive to shake!

Me hath she cast from high,

In fell disease I lie, and deathly fearing.So clear the flare

That first lit me

To seize

Her whom my soul believes;

If cad

Sneaks,

Blabs, slanders, my joy

Counts little fee

Baits

And their hates.

_____I scorn their perk

_____And preen, at ease.

Disburse

Can she, and wake

Such firm delights,

That I

Am hers, froth, lees

Bigod! from toe to earring.Amor, look yare!

Know certainly

The keys:

How she thy suit receives;

No add Piques.

'Twere folly to annoy I'm true, so dree

Fates;

No debates

_____Shake me, nor jerk,

_____My verities

Turn terse,

And yet I ache;

Her lips, not snows that fly

Have potencies

To slake, to cool my searing.Behold my prayer,

(Or company

Of these)

Seeks whom such height achieves;

Well clad

Seeks

Her, and would not cloy.

Heart apertly

States

Thought. Hope waits

_____'Gainst death to irk:

_____False brevities

And worse!

To her I raik,

Sole her; all others' dry

Felicities

I count not worth the leering.Ah, fair face, where,

Each quality

But frees

One pride-shaft more, that cleaves

Me; mad frieks

(O' thy beck) destroy,

And mockery

Baits

Me, and rates.

_____Yet I not shirk

_____Thy velleities,

Averse

Me not, nor slake

Desire.

God draws not nigh

To Dome, with pleas

Wherein's so little veering.Now chant prepare,

And melody

To please

The king, who'll judge thy sheaves.

Worth, sad,

Sneaks

Here; double employ

Hath there.

Get thee

Plates

Full, and cates,

_____Gifts, go! Nor lurk

_____Here till decrees

Reverse,

And ring thou take

Straight t'Arago I'd ply

Cross the wide seas

But 'Rome' disturbs my hearing.At midnight mirk

In secrecies I nurse

My served make

In heart; nor try

My melodies

At other's door not mearing.Ezra Pound: Near Perigord (1915)

I

You'd have men's hearts up from the dust

And tell their secrets, Messire Cino,

Right enough? Then read between the lines of Uc St. Cire,

Solve me the riddle, for you know the tale.Bertrans, En Bertrans, left a fine canzone:

"Maent, I love you, you have turned me out.

The voice at Montfort, Lady Agnes' hair,

Bel Miral's stature, the vicountess' throat,

Set all together, are not worthy of you..."

And all the while you sing out that canzone,

Think you that Maent lived at Montaignac,

One at Chalais, another at Malemort...

for every lady a castle,

Each place strong....Tairiran held hall in Montaignac,

His brother-in-law was all there was of power

In Perigord...

And our En Bertrans was in Altafort,

Hub of the wheel, the stirrer-up of strife,

As caught by Dante in the last wallow of hell -...How would you live, with neighbors set about you -...

What could he do but play the desperate chess,

And stir old grudges?..._____Take the whole man, and ravel out the story.

He loved this lady in castle Montaignac?

The castle flanked him - he had need of it...

And Maent failed him? Or saw through the scheme?_____"Papiol,

Go forthright singing...

There is a throat; ah, there are two white hands;

There is a trellis full of early roses,

And all my heart is bound about with love...."_____Is it a love poem? Did he sing of war?

Is it an intrigue to run subtly out,

Born of a jongleur's tongue, freely to pass

Up and about and in and out the land,

Mark him a craftsman and a strategist?...Oh, there is precedent, legal tradition,

To sing one thing when your song means another,

"Et albirar ab lor bordon -"...

What is Sir Bertrans' singing?Maent, Maent, and yet again Maent,

Or war and broken heaumes and politics?II

_____End fact. Try fiction. Let us say we see

En Bertrans, a tower-room at Hautefort,

Sunset, the ribbon-like road lies, in red cross-light,

South toward Montaignac, and he bends at a table

Scribbling, swearing between his teeth, by his left hand

Lie little strips of parchment covered over,

Scratched and erased with al and ochaisos..._____We come to Ventadour

In the mid love court, he sings out the canzon,

No one hears save Arrimon Luc D'Esparo -

No one hears aught save the gracious sound of compliments.

Sir Arrimon counts on his fingers, Montfort,

Rochecouart, Chalais, the rest, the tactic,

Malemort, guesses beneath, sends word to Coeur de Lion:The compact, de Born smoked out, trees felled

About his castle, cattle driven out!

Or no one sees it, and En Bertrans prospered?...Plantagenet puts the riddle: "Did he love her?"

And Arnaut parries: "Did he love your sister?

True, he has praised her, but in some opinion

He wrote that praise only to show he had

The favor of your party, had been well received."..."Say that he saw the castles, say that he loved Maent!"

"Say that he loved her, does it solve the riddle?"And we can leave the talk till Dante writes:

Surely I saw, and still before my eyes

Goes on that headless trunk, that bears for light

Its own head swinging, gripped by the dead hair,

And like a swinging lamp that says, "Ah me!

I severed men, my head and heart

Ye see here severed, my life's counterpart."Or take En Bertrans?

III

I loved a woman. The stars fell from heaven.

And always our two natures were in strife...*And great wings beat above us in the twilight,

And the great wheels in heaven

Bore us together... surging... and apart...

Believing we should meet with lips and hands.High, high and sure... and then the counterthrust:

"Why do you love me? Will you always love me?

But I am like the grass, I can not love you."

Or, "Love, and I love and love you,

And hate your mind, not you, your soul, your hands."..._____There shut up in his castle, Tairiran's,

She who had nor ears nor tongue save in her hands,

Gone - ah, gone - untouched, unreachable!

She who could never live save through one person,

She who could never speak save to one person,

And all the rest of her a shifting change,

A broken bundle of mirrors...![* These two lines Pound excised from the text in later editions, but I found them musically attractive. Most of the ellipses indicate passages I omitted, but a couple are in the original.]